From “Down Devon Way’ by S. P. B. Mais

I spent a happy evening at the “Chichester Arms” at Mortehoe, a white-washed inn of great antiquity. Tom Parker, who year after year looks after the two donkeys on Woolacombe beach, told me that one of them, Mary, had died on her legs at the age of twenty-seven just a month before.

“And my poor father,” he went on, “who died last autumn, said to me with his dying breath, “Mary’ll not live twelve month’ after me” – and me old dad was right.”

He invited me to attend the quarterly rocket-apparatus display of the Mortehoe Life-Saving Association the next day.

“There be no reg’lar coastguard,” he said. “We be auxiliary. I’m in charge, an’ there be twenty-two men to be drilled under me. Yew putt on your riding-breeches, me deurr, and us’ll give ‘ee a ride in breeches-buoy from ship’s mast to zemetery: twull be dree hundred yards, zure ‘nuff.”

That sounded an excellent idea to me, but I was unlucky.

The next afternoon, a perfect cloudless day of June, I endeavoured to be on Morte Hill at 2.30. I was too late. Exactly at 2.30 from below I saw on the sky-line a little group of men in shirt-sleeves, and then came a puff of smoke as the maroon was fired, and I ran up the hill to find about a dozen men in shirt-sleeves with numbered armlets on their arms pulling on a rope.

“Ted landed right on mast-head,” I heard on all sides.

Tom Parker, in his neat Sunday suit of brown, stood in the middle giving directions, and three officers in naval uniforms and a multiplicity of war medals stood giving contradictory orders and calling each other “Mr.”.

“Turn round, seven and three. Turn around all, and run away with it, lads,” was the first order I heard. Some three hundred yards away stood a look-out pole on the hilltop. Suspended above the valley ran a number of ropes, one of which the amateur coastguards were being implored to haul.

Number three – a humorous athlete in red-and-black football-jersey and motor mechanic’s overalls – was left to pull one rope alone, while the rest mysteriously were told off to do something with another rope, called the whip.

“Now, even numbers to the right whip, lads.”

These others consisted of a couple of farm-hands, the sweep, two stolid elders who might have been publicans or grocers, and young men in corduroys: as typical a collection of villagers as ever you’d meet. They might have been the village cricket eleven out for net practice. One group began attaching the breeches-buoy to a rope.

The breeches-buoy was a lifebelt with a sort of trouser-leg attachment. This was slowly being hauled up towards the mast-head, making a noise exactly like a hay-mower. I saw a man start to climb this mast.

“Now, numbers five, seven, and nine, start to put up the tripod.”

Three men started to erect a triangle of iron poles, and behind it other men performed complicated evolutions with ropes and a pulley.

“Number one, go back to anchor!” shouted one of the officers.

“Better have a half-hitch,” growled somebody.

Red flags were waved from both ends.

The man on the mast-head entered the breeches-buoy, committed himself to the rope, and after spinning round like a top came sailing high over the grass towards us, while our local motor-mechanic Bert Yeo, donkey-man Tom Parker, fish-merchant Ted Conybeare, and the rest pulled with a will.

But in spite of the tripod, the intricate pulley, the whips, commands, and counter-commands from the officers in uniform, the rescued man stopped suddenly in mid air, his legs dangling through the holes in the breeches-buoy, and then inconsequently came on by slow jerks until he reached a steep bank, whereupon he elected to walk towards his rescuer, who was encased in a cork lifebelt.

They met like Livingstone and Stanley, most affectionately, and in a few moments the rescued man lay stretched out inert on a tarpaulin sheet. He put up so good a show of inaction that I thought he was really exhausted.

Tom Parker knelt on him and, pressing in his ribs, said, “One, two, three” – pause – “four, five” – the senior officer standing over him.

“I don’t quite agree with that,” he said, and himself knelt on the inert man and gave an illustration of how to pump water out of a man’s lungs.

“And what would you do now?” asked the Inspecting Officer.

“Rub ‘en’s arms thiccy way.”

“Right!”

“Not holding ‘em up, ‘cos the effort may be too great for the heart.”

“What then?”

“Let ‘en bide vur an hour.”

“No,” interrupted one of the bystanders. “Hot-water bottles at arm-pits, thighs and soles of veet.”

“Then let ‘en bide vur an hour.”

“Why?”

“’Cos if ‘en moved ‘en, effort might stop heart ticken’ orver.”

“Quite right. And what then?”

“I’d give ‘en a drink.”

The Inspecting Officer asked the rest of the rescue-party whether they agreed with that. They agreed unanimously. He laughed.

“Everybody around here wants to give the man something to drink, but if you give him alcohol it may set the heart racing too fast. You look out for his wanting to be sick. If he wants to be sick he’s getting better.”

“I’d give ‘en tea. He’d be terrible cold lying there,” said someone.

The rescued man, tired of lying inert, now rose, and the Inspecting Officer made a polite speech of congratulation and disappeared – “ … For the drink he’d deny to a drowning man,” as one of the party said.

Then began a most complicated business of hauling in and coiling up the ropes into wooden boxes. This caused endless confusion and shoutings and tangles.

At the end of one rope I saw a wooden board attached with advice in four languages – French, Dutch, German, and English.

I read, “Fasten tail-block to lower mast well up. If masts gone, then to best place handy.”

I thought of this treacherous deadly Morte Point in a sou’-west gale on a winter’s night, and the wrecked ship’s masts gone, and these men called out from their beds to save the lives of drowning sailors.

It seemed incredible that anybody would stand a chance of being saved, and yet the Inspecting Officer had told me privately what he told the men publicly – that their standard of efficiency was high.

“It’s an odd thing,” he said to me, “but they’re always better if they’re tradesmen or farm-hands. The longshoreman’s no good – he thinks he knows it all, and won’t be taught; while the grocer, baker and milkman are as keen as mustard and eager to learn.”

I turned to watch the competition for throwing the lead, each of the party being limited to one throw of the leaded stick, which was attached to a long string, which in its turn was tied to one leg of the thrower.

Number three, the footballer, took infinite pains to coil his rope lightly, to get the back of his hand in front and only the crook of his forefinger holding the loop; then he gave an easy jerk, and the lead went sailing high into the air, over the line some twenty yards ahead, and away on, to be measured as a throw of thirty-eight yards.

“I never zeed a zhot like it in all my years,” said one of the older men – and, indeed, the feat had the grace of an Olympic event. “I’ll bet ‘ee a pint no one’ll touch that.” There were no takers.

But Yeo was modest, and turned towards the garage behind the hill, where his services were needed. He had won half-a-crown for his throw.

And at that moment came the counter-attraction of half a dozen porpoises leaping out of the sea in the calm bay below. At one moment they seemed to be within a few yards of the unconscious swimmers from the beach; the next they were racing towards Baggy Point.

“Plenty of zalmon in Bay, I reckon, today,” said one of the life-savers.

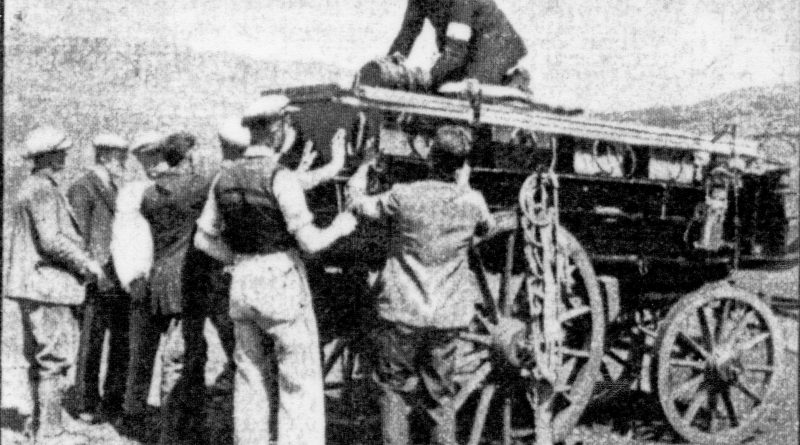

The ropes coiled under their boxes, there was a pause. Number five was missing, and without him the boxes could not be hauled on to the red-wheeled wagonette which contained the life-saving gear.

Eventually he was found, and the last I saw of the gang was a sharp silhouette against the skyline of the old horse pulling the heavy cart down the steep grassy slope, while the team of men, still roped together, pulled her back from behind.

Rocket-practice at Mortehoe is a rare event, but it is an event not to be missed.